Over the past five years, there have been multiple predictions about the trajectory of Nigerian music consumption. It became increasingly apparent that the most popular Afrobeats tunes of the late 2010s and early 2020s were reaching a point of exhaustion. Younger consumers began to crave more dynamics, more flavour something uniquely different and captivating beyond the staple sounds they had grown used to. In their search for freshness, several brilliant artists turned back to their roots and rediscovered the evergreen, ever-innovative, ever-melodic world of Fuji music.

Mind you, Fuji never went extinct. It was simply outperformed by a younger generation who, at the time, sought new excitement in hip-hop, R&B, and eventually Afrobeats. One could also blame the heavy influence of Westernisation for this shift. Yet, despite these changes, the collaboration and infusion of Fuji into Afrobeats never stopped. Fuji music has always had a fluid nature that ensured its relevance across decades. At different points in their careers, the likes of Adewale Ayuba, Saheed Osupa, Pasuma, and K1 De Ultimate collaborated with artists outside the genre. Jazzman Olofin’s mega hit Raise the roof featured Adewale Ayuba.

Fuji transcends its talking drums, sekere, omele, and other percussion-heavy instruments. It is equally defined by its vocal identity a fluctuating, dynamic pitch that often rises into crescendos, shaped heavily by the tonality of the Yoruba language. Some Afrobeats songs over the years have been deeply influenced by Fuji. Towards the late 2000s, 9ice became one of the most sought-after artists in Nigeria, and it is clear that hits like Gongo Aso widely named one of the greatest Afrobeats songs ever and Gbamu Gbamu carried strong Fuji influence. He has always referred to himself as a Fuji artist, and in 2012 he was featured on Saheed Osupa’s Oj Mi Ri.Olu Maintain’s Yahooze can also easily be regarded as a Fuji song with hip-hop elements.

The early 2010s produced Konga’s Kabakaba, which featured the late rapper Dagrin and Fuji artist Remi Aluko. The track quickly became a nationwide hit. So did Reminisce’s Kako Bi Chicken, which showed how rap/hip-hop could blend effortlessly with Fuji. Wizkid’s Pakurumo also stood out as a youthful Afrobeats/Fuji fusion. On Olamide’s second album Baddest Guy Ever Liveth, he sampled K1 De Ultimate’s Omo Anifowose on the emotional rap-Fuji hybrid Anifowose. L.A.X also emerged with a distinct Fuji-like vocal texture that shined on Wizkid’s Caro.

Throughout the 2010s, numerous hits carried Fuji elements. Olamide especially stood out with Eleda Mi, Wo, Bobo, Omo Abulesowo, Indomie and more. Wande Coal’s Ashimapeyin and Iskaba were equally embodiment of Fuji sound. Pasuma made a bold crossover run in 2016 with his Afrobeats-leaning album My World, featuring Olamide, Tiwa Savage, Phyno, Oritse Femi, Qdot and others. Obesere followed in 2017 with his album, Hip Hop Mafia, featuring Olamide, Timaya and Reminisce; he also featured Zlatan on the remix of his viral hit Egungun. Small Doctor further embodied the Fuji-Afrobeats hybrid with hits like Gbera, This Year, and Penalty.

The 2020s marked the rise of Bella Shmurda. His High Tension EP leaned heavily on Afrobeats production but carried unmistakable Fuji-inspired vocalisations. In 2020, K1 De Ultimate took a bold step by remastering and re-recording several classics into a modern EP, Fuji The Sound. Thanks to producer Mystro, the project infused Afrobeats elements into Fuji, introducing the songs to a younger audience. This EP birthed the global resurgence of Ade Ori Okin, now a massive international hit.

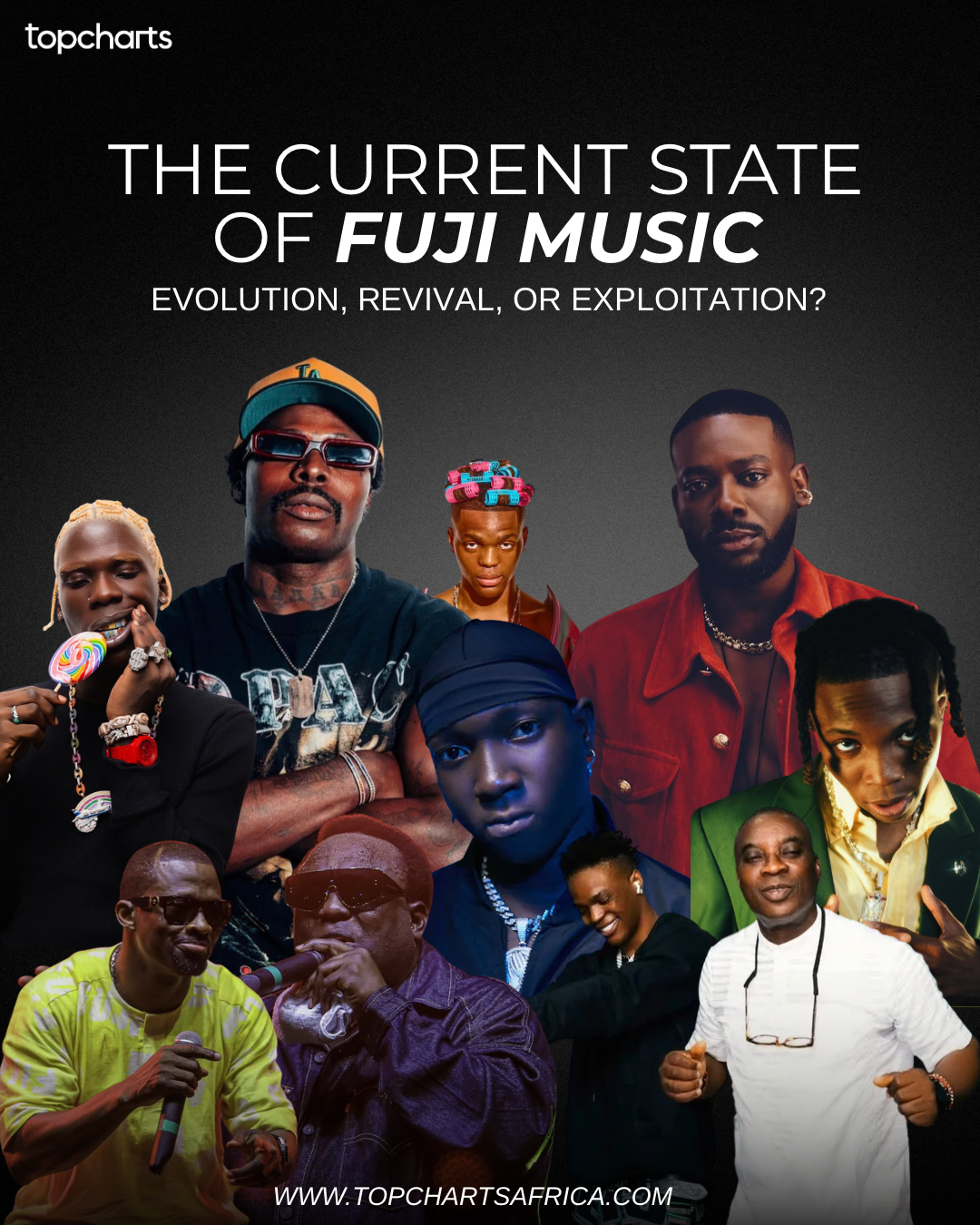

Fast-forward to 2024: the itch the new generation had been feeling became clearer. The remedy was a deeper, unapologetic infusion of Fuji into Afrobeats.With the ascension of Asake and Seyi Vibez, who embraced and married Fuji with Afrobeats, taking it to unprecedented heights. They blended it into a unique sonic identity that became a global phenomenon, influencing countless artists. Asake, with Palazzo, Sungba, Terminator, and 2:30, helped solidify “Afro-Fuji” as a legitimate subgenre.

By early 2024, Spotify was already reporting 175%+ growth in Fuji streaming (Q1 2024 vs Q1 2023), and BusinessDay noted that Gen Z listeners were at the centre of this revival. Fuji wasn’t just surviving it was trending, charting, and being algorithmically rediscovered across continents.

Now, in 2025, Nigerian musicians across the board are identifying more openly with Fuji. Street-affiliated artists from the South West embraced it early due to its resonance with their audience Portable, T.I Blaze, Tml Vibes, Balloranking, Badboi OML, Oshamo and others. Portable’s entire catalogue, from Zazoo Zeh to Clear, is steeped in Fuji energy. T.I Blaze’s Kilo Kilo, Oshamo’s New Fuji, and Badboi OML’s Wasiu Ayinde, a tribute to K1 De Ultimate’s 1997 Talazo style are defining this new era.

TikTok trends also revived older Fuji hits such as Ayuba’s Koloba, Osupa’s Jokoo Sibe, Reliable Pt. 5, Everlasting, and K1’s Vivid Imagination, proving the genre’s timeless appeal.

Almost every major Afrobeats album in 2025 contains Fuji-influenced tracks Falz’s No Less (sampling Barrister’s Fuji Garbage), Bella Shmurda’s Fuji Mix featuring K1, Rybena’s Dewale featuring Saheed Osupa, and more.

The biggest talking points have been Adekunle Gold’s Fuji album and Seyi Vibez’s Fuji Moto. Naming an entire album after the genre was a bold move that stirred curiosity, especially among Fuji loyalists. However, Adekunle Gold’s album fell below expectations because few songs truly embodied Fuji. This earned him criticism from fans and culture watchers. In an attempt to salvage the moment, he released a remix and video for Many People featuring Yinka Ayefele, sampling Mi O Mo Ju Orin Lo, and later featuring Adewale Ayuba referencing his 1994 Fuji Musik created a nostalgic full-circle moment. The music video with its vibrant, 90s-styled Fuji aesthetics delighted fans. The same could be said of Badboi OML’s Wasiu Ayinde video.

Seyi Vibez’s Fuji Moto delivered more Fuji elements, but the Japanese and East Asian-themed visual branding left many confused. One would think Fuji is an Asian genre. The same applies to Adekunle Gold’s cowboy-styled cover art. It raises the question: Are these artists genuinely embracing Fuji holistically, or simply trimming out the interesting parts for aesthetic appeal?

This year alone, Fuji has enjoyed immense global attention. Burna Boy, on Complex’s God Talk with Roger Federer, revealed that Saheed Osupa is his favourite artist and expressed deep admiration for the Fuji genre.

All of this leads to an important question: Is the Fuji genre truly progressing, or is it merely being used as a trend to milk? Nigerian artists are incredibly versatile they glamorise, globalise, and then eventually abandon sounds when they tire of them. We saw this with the “Pon Pon” era (2014–2017), and again with “Amapiano” (2020–2024). When they were done, they passed the sound back to its originators. Is Fuji next?

Evolution is inevitable. Fuji has evolved from its earliest days, and even among its biggest stars, each carved out a unique style and legacy. But one major setback remains: the same names and faces have dominated the genre for decades. The last time a “full-blooded” Fuji artist broke into the mainstream was roughly 20 years ago with Shanko Rasheed. Recently, Tiri Leather gained attention largely due to controversies.

This threatened stagnation is partly because success within Fuji heavily relies on live shows and physical performances. The audience tends to recycle the same familiar stars unless a newcomer is endorsed by a veteran often after years of apprenticeship and in some cases will still have to introduce themselves by their boss’s name K1 De Ultimate was once known as Wasiu Ayinde Barrister; Taye Currency introduced himself as Taye Pasuma until he gained enough footing.

Today, countless underground Fuji artists are struggling to break out. Many lack the modern sophistication required in today’s entertainment industry. Some still depend on CD sales and local performances, without social media presence, DSP uploads, marketing strategies, or the digital education needed to thrive.

While I’ve always believed that every musician should cultivate their own audience, the Fuji genre cannot evolve without deliberate effort from its underground community. There must be a shift an openness to technology, branding, and modern music economics.

Some might argue that Afrobeats artists benefiting from Fuji legends is unfair to underground Fuji acts. But the industry will always follow whoever has momentum. The game is the game and for Fuji to survive this new era, its grassroots must be re-educated, reorganised, and re-energised.